The galaxy is a big place. Within several of its planets lay your remaining clones, beings ripped from your body, causing a gradual cellular degeneration should you not locate and extract the vital fluid from each before it’s too late. There are just five left, but you don’t know where they are, and there are thousands of planets to explore. The outstanding clones, or numbers, can only be found by interrogating many of the alien species that populate the galaxy. There’s just one problem: you have no idea what they are saying.

It sounds like the premise of that weird indie game you’ve got on your Steam wishlist. But it isn’t. This is the plot of Captain Blood, the huge hit of 1988 from French publisher ERE Informatique. And like many games of the time, it began life as a tech demo. “One day, I met Didier Bouchon at an exhibition,” begins Philippe Ulrich, lead designer on Captain Blood. “We quickly came to like each other, so when I got an Atari ST before anyone else, I gave it to Didier to explore the innards of this new beast.” Neither had much commercial computer game design or programming experience, but when Ulrich returned to his friend a few weeks later, the seed of their first game together was sown. “I visited him in his den, and he had started programming a map generated by a fractal seed on the ST. After a few glasses of Brouilly and some drawings on a restaurant tablecloth, we imagined putting this map on a sphere.” From this seed, the pair could store a whole galaxy’s worth of planets within the ST’s 512K floppy disk, using a procedural terrain generator to create each unique world.

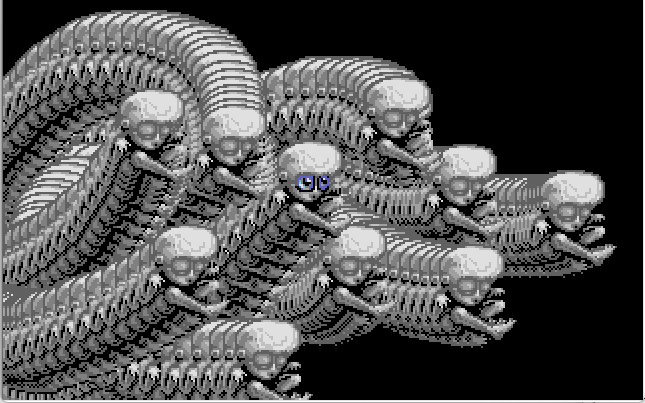

These worlds are represented by a scrolling landscape and canyon. And, at the end of some – rather conveniently – sits an alien, ready to converse with Captain Blood. Remember, Blood is trying to locate the five remaining clones and obtain their vital fluid so he may live. “The idea of a hero who accidentally clones himself and must find his clones came naturally,” explains Ulrich. “We’d been fed comics, novels and cyberpunk cinema to the rhythm of Kraftwerk’s impeccable beat.”

Captain Blood’s 11-page short story begins not in outer space but on Earth, at the home of unkempt computer programmer and master games player Bob Morlok. A chance encounter with Charles Darwin (stay with me) inspires Morlok to create, within his game, the Ark, a spaceship fitted with an organic onboard computer and his own digital double, Captain Blood. Finally, months later, Morlok is ready to test his new game. He types out the momentous instruction – RUN – and instantly winks out of existence, transported into his game. Then, following a nasty hyperspace accident, 30 clones are extricated from the Captain, an army of fakes spread over the galaxy. Blood has one choice: track them all down, launch a probe to the planet’s surface, teleport them in turn into his cryonisation container, the Fridgitorium, and extract the vital fluid, disintegrating the clone in the process. But first he has to find them, and here, away from the fancy fractal graphics, is the core of Captain Blood.